The Healing Qualities of Architecture

Towards a physiological approach of healthcare spaces

Towards a physiological approach of healthcare spaces

A pioneer with plenty of common sense

In 1854, Florence Nightingale disembarked in Turkey to work as a nurse in the hospital of Escurati. There, the wounded British soldiers from Crimea were more likely to die from cholera, dysentery and infections than due to warfare injuries. The young nurse saved many lives by introducing measures such as separating the ill in different wards with cross ventilation, adding distance between beds, and improving the overall hygiene. The Nightingale discovered that hospital architecture and design was a key issue to improve patient’s health.

Florence was a visionary in understanding the environmental impact on patients’ health. In fact, she was a pioneer on the concept of ‘healing environment’ – in how to manipulate the environment to make it become therapeutic. In her book Notes on Hospitals (1859), she wrote: “The appropriate adjustments in the environment can avoid illnesses”.

The healing qualities of nature

Twenty years after the loss of Florence Nightingale, the architects Alvar Aalto and Aino Marsio designed the Sanatorium of Paimio, a patient-centred tuberculosis treatment clinic, set amidst a Finnish forest. Antibiotics didn’t exist then and the architects, aware that the sun was a key factor to recover from this illness, based their design by making the most of daylight, space ventilation and views to nature. Both the location and the orientation of the various volumes are ruled by this idea. The hospitalization block is equipped with large terraces above the south façade –where patients spent long hours in the open-air– and was equipped with some of the essential elements of Design Centred on People (DCP), such as large windows with views to nature seen from the bed, custom designed furniture or colourful walls and ceilings.

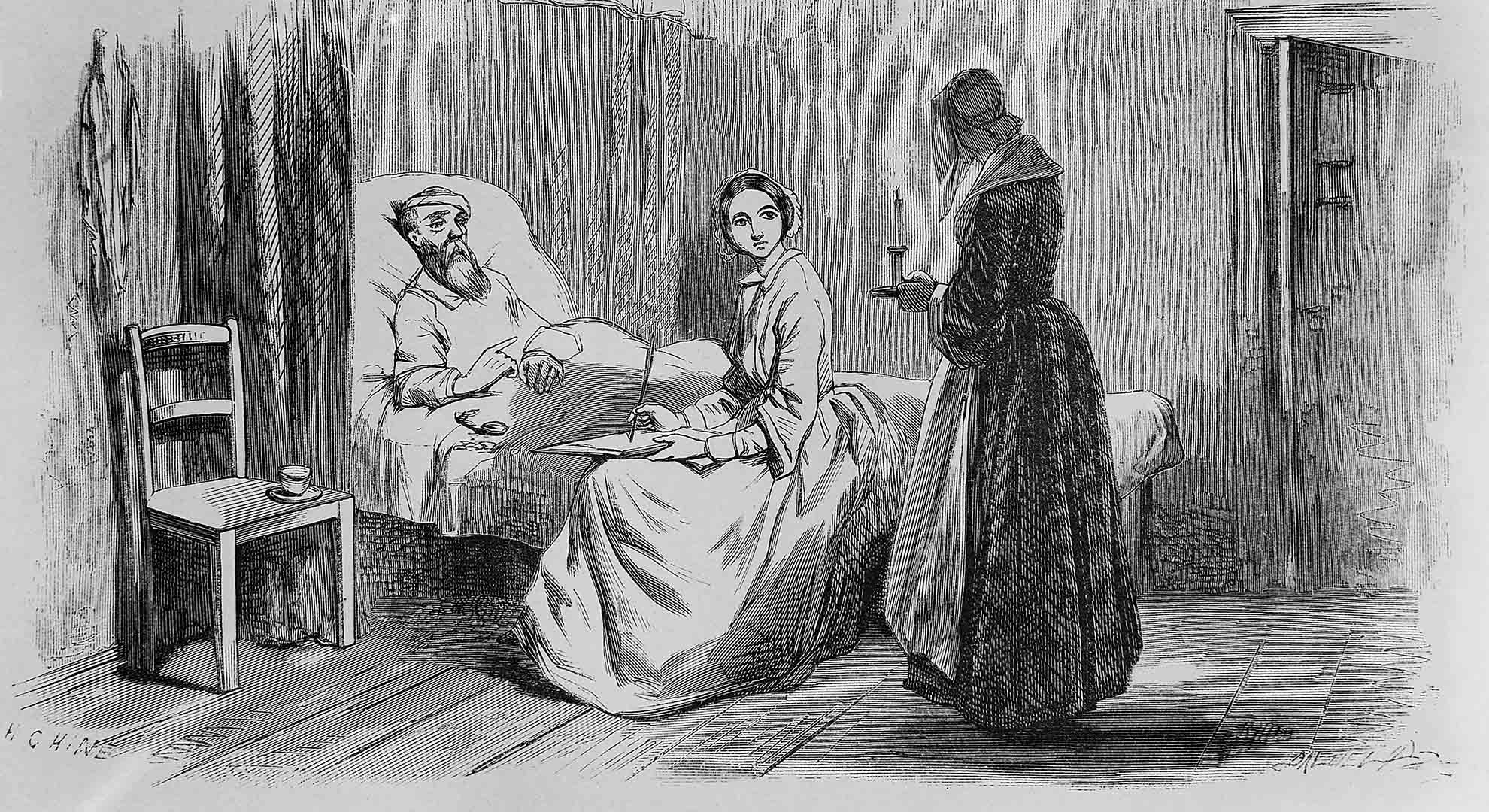

Florence Nightingale and the dying soldier. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The positive effects of nature, backed by scientific evidence

The claim that the environment has an influence on patients’ well-being seems quite sensible and reasonable today, but it wasn’t until 1984 that a scientific position is taken on the matter. Between 1972 and 1981, professor Roger Ulrich gathered data of patients recovering after an operation in a suburban hospital in Pennsylvania. The idea was to determine whether the patient could have a measurable positive influence in his recovery if they were given a room with views of nature. The result showed that 23 patients who were assigned a room looking to nature had shorter postoperative stays, fewer painkillers and had less negative reports from nurses than other 23 patients who were staying in similar rooms but with their windows facing a brick building. The publication of the research in the prestigious magazine Science (View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Ulrich, 1984) created a greater awareness of the impact of space and hospital architecture on patients’ physical condition and state of mind.

Ever since there has been an ever-growing number of studies on similar issues that support this idea, which would also serve to reduce healthcare expenses.

Ulrich’s study gave way to the development of what we now know as EBD (Evidence Based Design), which is defined as the decision-making process over the built environment based on thorough and reliable research, aimed at attaining the best results possible on health. This approach acknowledges how the design of the physical environment can alter the quality of the patient’s care and state of health. The emotional influence of space as a possible factor of physical healing is supporting by the World Health Organization’s definition of health: a state of physical, mental and social well-being, and not only the absence of disorders and illnesses. Elements such as sensorial comfort, noise reduction, biophilic design, human-centred design, sustainability or DBE are some of the tools that allow us to design healthy spaces.

Maternity room in the University Hospital of Getafe in Madrid, Spain, designed by Parra-Müller Arquitectura de Maternidades. Photo © Parra-Müller Arquitectura de Maternidades

Healthy, sustainable and comfortable spaces: generating health

But on the brink of the third decade of the twenty-first century, to only think about more healthy spaces is settling for too little. At this moment, beginning the post-antibiotic age, technology is riding on the horseback of artificial intelligence and hi-precision medicine, questioning the current hospital model. Now that the great challenges of humanity are focused on the urgency of looking after the planet; hospitals -and other buildings- must not only be sustainable but healthy and comfortable places, meeting users physical and emotional needs; buildings that not only don’t make us sicker but actually generate health.

A recent example of the capacity of improving the results in health is the area of natural birth at the hospital HM Nuevo Belén in Madrid, whose project we carried out at the studio. Equipped with three integral delivery rooms, waiting areas and auxiliary areas for the professionals, all was designed from a physiological point of view, to meet women’s and other users’ every need during the delivery process. From leaving enough space to move, the use of natural materials, light, sound and temperature regulation; to providing a non-hospital atmosphere or places where to store medical instrumentation out of sight, among others. As women kept giving birth with the traditional conditions in the rest of the hospital it was easy to compare the obstetric outcomes between both models with amazing conclusions over the new one: the rate of medical procedures decreased drastically, epidural use fell by a half thanks to having provided every room with a shower and dilatation bath, and C-sections dropped to a third of the rest of the hospital.

Our care spaces are crying out to broaden the scope. We can no longer settle for just controlling the illness but we also want to rid ourselves of the side effects derived from medical procedures, create environments and hospital architecture that soothe the patient and care for the professional while addressing the physical and emotional needs of society as a whole.

Main image: Delivery room at HM Nuevo Belén hospital, Madrid. Photo: © David Frutos